CarEnvy’s resident Russian explains why Russia generates so many car crash videos.

By Artem Barsukov

Russia has always been famous around the world for three of its exports: vodka, caviar, and suicidal novelists.

And guns. Lots and lots of guns.

Make that four exports, then. Yet, in the past couple of years, the country has firmly established itself as the world’s number one producer of the web’s latest craze: dashcam videos!

The phenomenon has been the talk of the Internet and beyond. CNN, NBC, and Jon Stewart have all done stories on it. Internet users the world over have come to learn the expressions blyad’, pizdets, suka, and other colourful words Russians use to express their emotions.

Mankind has been able to witness the crash of a massive meteorite over remote parts of Siberia from different angles — as if it were a live concert on some early DVD — thanks to the Russian dashcams.

And, of course, the phenomenon has also thrust a lot of everyday weirdness into the international spotlight such as horses on crosswalks, tanks on public roads, helicopters doing low flyovers above public highways — you name it — it’s all been posted on YouTube for the world to see.

Having never witnessed anything like this before, the Western world found itself stupefied, drowning in a myriad of inevitable questions and assumptions. One only needs to open up the YouTube comments for any Russian dashcam compilation to see what I mean. You can see these types of comments under virtually every video involving a car crash somewhere in Russia:

Why does every person seem to drive around with a dashcam?

Russians are the worst drivers in the world.

People in Russian cannot drive for shit.

Holy crap, is it illegal to *NOT* drink and drive in Russia?

And so on.

As someone who has spent 12 years of his life riding shotgun (and even attempted to drive) on Russian roads, I felt compelled to address these misconceptions and answer some of the questions my Western friends have been asking. I’ll start with the most obvious one.

What’s With All the Dashcams?

Indeed, why does seemingly everyone in Russia drive around with a dashcam strapped to their windshield?

The answer is simple: insurance fraud.

Here’s how it usually goes: you’re standing still on a red, minding your own business, when all of a sudden the car in front of you changes gears and reverses straight into you. Or someone cuts you off at high speed and slams their brakes. Or you stop at a crosswalk, and a pedestrian beautifully spreads himself across your hood, as if he is performing part of the Swan Lake. In every case, the “victim” will allege that you have caused the accident and try to have your insurance pay them a lofty compensation.

Most of the time, it simply enough to point to a dashcam to have the enthusiasm of the “victim” quickly extinguished. If you run into a persistent one, your dashcam video will usually settle the matters with the police and the insurance company.

Here are some typical road scams:

Typical scam involving a vehicle. Skip to 1:25 to see the action.

A compilation of scams involving pedestrians.

Do Russians Actually Suck at Driving?

I don’t usually come off as an über-patriot screaming “Aaaah mozerland!” every time someone criticizes Russia, but I do think that Russian drivers get more flak than they deserve on the Internet. There are a few reasons for that.

First, there is the selection bias.

Put simply, people only post videos that have some kind of an incident in them. You wouldn’t want to watch 2.5 minutes of some dude cruising around the streets of Krasnoyarsk, would you? As a result, what you usually see coming out of Russia are examples of truly bad driving.

Second, Russia has pretty rigorous driver training.

You have to learn to drive a manual. There are slalom and reversing exercises. And then there is the obligatory city and highway driving — except that this happens on the Russian roads. Many people have to take the road test several times before they pass. Of course, there is a not-insignificant number of people who simply bribe the authorities to pass the test, but they quickly learn the ropes on the roads. Which leads me into the third reason.

Third, driving in Russia is a constant challenge.

You don’t just sit back, turn on cruise control, and expect everyone to follow the traffic rules. No, you are constantly at war with everyone else on the road. You always have to be ready for the unexpected. I still remember the first advice my father gave me when teaching me to drive in Russia: “always think for the idiots on the road.” In Russia, your regular driving is looking at the nearest car and thinking: “Now, how can he screw me over?” You basically drive expecting others not to follow the rules.

Fourth, a lot of Russians still drive Ladas.

Which means your car has no power steering, no ABS, no EBD, no break assist, and no traction control. Oh, and the brakes are crap. It’s like being in charge of a nuclear power plant. Your car does not forgive mistakes.

Combine these factors, and you’ll realize that it takes an incredible amount of skill to drive in Russia. Russian drivers are always ready for emergencies, they are quite adept at evasive manoeuvres, and they have extremely fast reaction times. In other words, your average Russian driver is likely to be more skilled than your average Western driver.

So Why All the Accidents?

You can actually see the answer in most videos posted on YouTube. It’s the complete disregard for all traffic rules.

On your average Russian commute you are likely to see: close tailgating, abrupt lane changes without signalling, driving between lanes, disregard for traffic signs, disregard for traffic lights, crossing over the double solid line, and, of course, extreme — and I mean extreme — speeding. So, it isn’t just a disregard for the traffic rules. It’s more of a disregard for the elemental norms of safety.

You are probably thinking: this doesn’t make sense. What about the self-preservation instinct?

You are right, of course. None of the people you see doing stupid things in the videos actually intend to die. The answer lies in a unique cultural phenomenon known as avos’.

Avos’ roughly translates into English as “on the off-chance”, but it doesn’t quite capture the true meaning of the word (that the English language does not have a direct equivalent is in itself quite telling). It is a generic expression of fatalism that basically means: “I know I’m doing something very risky/against the rules, but I think it’ll be okay.” There is an old Russian joke that captures the phenomenon really well:

A semi trailer collides with a Lada at an intersection on an amber light. The police arrive and interview the drivers. They ask the driver of the Lada:

— What were you thinking when you were going through the intersection on an amber light?

— I thought I was going to make it.

— And what were you thinking, the semi driver?

— I was thinking: the hell you are going to make it.

You see this in virtually every car crash video. A Russian drivers engages in what he knows to be an unsafe manoeuvre, thinking “it’s not going to happen to me.” But, of course, it does. Here are just a few examples:

Passing several stationary vehicles. The other driver executes a turn without checking his mirrors.

Passing several vehicles at once in an oncoming lane.

Passing while in a blind curve — and crossing a solid line.

To be sure, this type of thinking is not entirely foreign to westerners. Many accidents — anywhere in the world — happen because someone chose to disregard safety rules thinking it’s going to be okay. It’s a question of degree. Russians usually go with their gut, rather than with the rule book.

Some may call it arrogance. Some may call it stupidity. But one thing is certain: it does not negate skill. It’s not a lack of pure skill, but rather a conscious disregard for traffic rules, that leads many in the West to believe that people in Russia are the world’s worst drivers.

The Avos’ Approach

You cannot blame the Western commentators, though. In the West, skill implies care. The two go hand-in-hand. A skilled professional is someone who relies not merely on raw talent and experience, but also on being careful in what they do. A skilled professional knows the rules and is prepared to follow them.

The way I see it, there are two fundamental approaches to managing complex and risky tasks. I call them “the procedural approach” and “the Avos’ approach.”

The procedural approach is common in the Anglo-Saxon and protestant cultures, as well as in Japan. The Swiss and the Germans, famous for always sticking to the rules, exemplify this type of behaviour. Its main postulate is simple: follow the procedure and you’ll never go wrong. There is a reason someone wrote the rules.

The Avos’ approach, perhaps better described as “the gut approach“, is more common in the Eastern cultures and, specifically, in Russia. Its main postulate is: rules are rules, but I think I know better. There is no way the guy who wrote the rulebook could foresee everything. You go with your gut, rather than the rules.

As an avid aviation enthusiast, I find the difference in the two approaches perfectly exemplified in the aviation world. Indeed, where else will you see two fundamentally different cultures clash if not in the international airspace?

There is one particularly tragic incident that provides a textbook example of the difference in the two approaches: the 2002 Überlingen mid-air collision between a Russian airliner an a DHL cargo jet over southern Germany.

Here is a little bit of background. Every modern plane is equipped with a so-called TCAS System. It’s essentially an air-to-air radar that monitors traffic around an aircraft. When two aircraft are on a collision course, the systems of the two aircraft will talk to each other, and a computerized voice will instruct one pilot to climb and the other to descend. In this case, the system correctly told the DHL plane to descend and the Russian plane to climb. The rules would dictate that you follow the TCAS’ directions. However, the Russian pilot was simultaneously being told by the air traffic controller to descend. The Russian pilot ignored the TCAS instructions and proceeded to initiate a descent, colliding with the DHL plane a few seconds later.

Yet, the gut approach does not always result in disasters. Quite on the contrary, it sometimes leads to miraculous escapes. In 2011, a Tupolev Tu-154M was taken out of storage for a test flight. Upon takeoff, control surfaces failed almost immediately. An eyewitness has posted a video of the whole incident on YouTube. You can see the plane rolling violently to both sides, its flightpath bearing no resemblance of ”straight and level” — or “stable”, for that matter. There was no checklist, no procedure for a failure of that magnitude. And yet, using nothing but their experience — and gut — the pilots have somehow managed to wrestle the stricken jet safely to the ground.

Therein lies the fundamental difference and the fundamental tradeoff between the two approaches.

Sure, you are going to be safer with the procedural approach in the vast majority of situations. But constantly following procedures destroys creativity.

When a truly unforeseen emergency strikes, there is often no checklist. All you’ve got is your gut, your instinct.

A person following the procedural approach, unable to come up with creative solutions, his fear compounded by the sudden absence of an always-available checklist, will likely fail to recover at that point. On the other hand, a person following the Avos’ approach will immediately rely on their gut — the only tool available in absence of a procedure — and will have a higher chance of salvaging the situation.

Unfortunately, the Avos’ approach also carries a significant downside: most of the time, the I-know-better attitude just doesn’t work. Quite simply, completely unforeseen emergencies do not happen all that often in real life. And if they do, in many cases there are fifteen different rules that can help prevent the situation altogether.

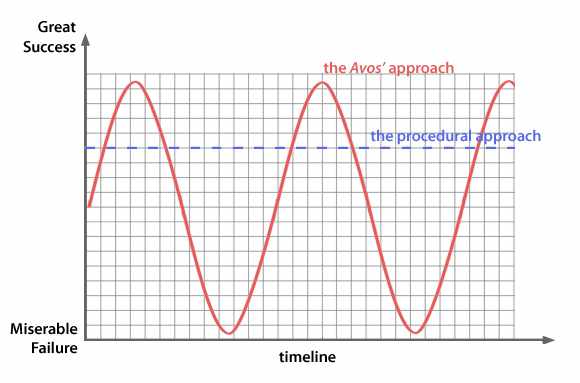

The Avos’ approach therefore usually results in either miraculous salvations or great catastrophes, with little middle ground in between. It is rarely consistent. Meanwhile, a person following the procedural approach may not make the impossible saves the gut guy will, but at least he will be consistent in achieving a decent, “safe” result. If you graph it, it looks something like this:

In the long run, then, following the rules seems to be a safer choice. But will this approach find favour in Russia?

In the long run, then, following the rules seems to be a safer choice. But will this approach find favour in Russia?

I doubt it. Trusting your gut and hoping for the best is an aspect of the Russian culture that has been cultivated over generations, and it will not go away easily. Indeed, most Russians wouldn’t want it to go away. Adopting the procedural approach isn’t simply doing what’s safer — it’s akin to altering the entire national psyche.

And as long as the threat of insurance fraud continues to linger over Russian drivers, we can expect more devastating crashes and miraculous near-misses pouring out on the interwebz from the vast expanses of 1/8ths of the Earth’s land mass.