The Chevy Volt.

Ah yes. The very embodiment of the Obama Administration’s public appeasement after GM’s bailout in 2008. For years thereafter, the Volt wrapped itself in the untouchable US flag and became a symbol of innovation, risk-taking, and taxpayer dollars. But now the dust has settled and the car is here: for sale at your local dealership, miles away from the world of partisan bickering, if not public relations spin. It’s been four long years since we were promised a revolution. Has the wait been worth it?

Much like the President, I had high, but not foolishly untempered expectations of this American. With its 16-kWh battery and 60km all-EV range, Chevy claims the Volt will ferry 78% of us to work and back without a single drop of Alberta’s famous bitumen. Of course, since it only seats four people, each family will need their own, but you get the idea. General Motors, the profligate statue of American excess, couldn’t (or wouldn’t) offer us complete freedom from oil. Not quite. For those “once-in-a-whiles” – those fishing trips, those trips to the farm, and those trips to the mountains – there’s an 83hp 1.4L “range-extender” (read: engine).

As an igloo-dwelling urbanite with no plug-in at home or office, the Volt isn’t for me. But that just makes its forbidden fruit that much sweeter. While in Vancouver recently, accompanying my fiancée on a “continuing education” getaway (not as miserable as it sounds), I sipped the extended-range-electric nectar and indulged in a “once-in-a-while”. But enough quotation marks.

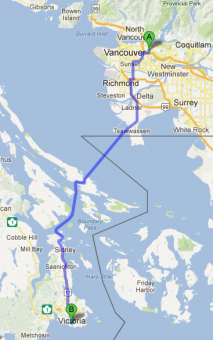

With keys in hand, I took full advantage of the Voltec (big battery+little engine) to be as spontaneous as possible and set my course for the British Columbia Parliament Building in Victoria, on Vancouver Island. The copper-topped castle was a perfect excuse to ride the ferries I remembered so fondly from my time at Camp Miriam on Gabriola Island, just 5km east of Vancouver Island. From Vancouver to Victoria and back was 140km of driving on top of the two 90-minute ferry rides. How much of that could I run on pure electricity? What would the Volt be like when the engine turned on? I wondered…

Driving south from the pick-up spot in Burnaby, just east of Vancouver proper, I waded through steady rains and an even steadier stoplights towards the Tsawwassen Ferry Terminal 40km away. The windshield wipers tried their damnedest to keep up with the rain but frequently fell behind, diminishing my visibility in a car already marred by a cocooning wealth of plastic, leather, and (probably not enough) glass. Unlike in other electric cars (read: Nissan Leaf), any anxiety I had wasn’t from lack of range, GM’s little engine made sure of that, it was more from confusion as to the non-flakey nature of the precipitation. It was just so… wet.

Driving south from the pick-up spot in Burnaby, just east of Vancouver proper, I waded through steady rains and an even steadier stoplights towards the Tsawwassen Ferry Terminal 40km away. The windshield wipers tried their damnedest to keep up with the rain but frequently fell behind, diminishing my visibility in a car already marred by a cocooning wealth of plastic, leather, and (probably not enough) glass. Unlike in other electric cars (read: Nissan Leaf), any anxiety I had wasn’t from lack of range, GM’s little engine made sure of that, it was more from confusion as to the non-flakey nature of the precipitation. It was just so… wet.

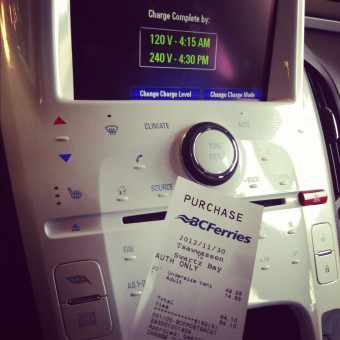

Arriving at the terminal a full hour before the 1pm departure, I grabbed a slice of veggie pizza at the Quay Market and watched the cars line-up in enormous strings. The Volt had only 2km of full EV range showing on the 7” screen behind the steering wheel but I wasn’t the least bit worried. Although I had 30km to go from the Vancouver Island-side terminal to the gothic Parliament, I was looking forward to charging my battery-sucking iPhone 5, keeping the seats heated, and making good time without any further charging. I sat there, listening to the audiobook of Nassim Nicholas  Taleb’s Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder

Taleb’s Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder(link to Amazon), the third in his trilogy on optionality, following 2001’s Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets

and 2008’s The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. The Black Swan, when I read it exactly one year ago, profoundly changed my worldview. To say that I was looking forward to digesting Antifragile would be a gross understatement.

What’s antifragility? It’s a made-up word for the things that benefit from volatility, unlike fragile things that are harmed by unpredictable circumstances [for more depth: video interview with Taleb]. Examples of antifragility are typically organic – like our bones – that have a convexity to volatility. What is manufactured by modern man, and therefore over-optimized towards “efficiency” – things like traffic, economies, and technology – are the opposite. When volatility strikes, and it eventually will, BOOM! Down goes anything over-optimized. (Unless it’s bailed out).

Nassim Taleb, with the erudition only a Levantine polyglot steeped in the Classics could have, categorically rejects efficiency and expounds redundancy and protection from the unknowable. He believes that an over-reliance on mathematical models has fragilized our Western society. He leaves no topic untouched: medicine, finance, and child-rearing all feel his wrath. And my goodness does he make a strong case! All this was flowing through my soggy cortex as I studied the motionless Volt sitting in line to board.

Nassim Taleb, with the erudition only a Levantine polyglot steeped in the Classics could have, categorically rejects efficiency and expounds redundancy and protection from the unknowable. He believes that an over-reliance on mathematical models has fragilized our Western society. He leaves no topic untouched: medicine, finance, and child-rearing all feel his wrath. And my goodness does he make a strong case! All this was flowing through my soggy cortex as I studied the motionless Volt sitting in line to board.

Then it hit me:

If you’re looking for an “electric” car that can handle life’s unpredictabilities, the Volt is it! No plug-in? No problem! That the Volt comes from a company synonymous with go-anywhere-do-anything trucks should come as no surprise.

The fully-electric Nissan Leaf, often seen as the Volt’s greatest competitor, is far more fragile. Nissan’s own website acknowledges that the same impromptu journey from Vancouver to Victoria would’ve been impossible in their electric car. The Volt didn’t care if there was no charging point. It made full use of its small gas-powered engine and a vast network of gas stations already dotting the landscape. Let’s not forget that the distances between North American populations are nothing to sneeze at, yet whether the spontaneous destination was Victoria or Seattle or the Parque Nacional Tortuguero, the Volt was ready. It was practically antifragile.

And it felt it. The doors were weighty, the sound insulation was upmarket, and the details were premium. The charging port opened with a sophisticated waft using the key fob, the side mirrors were elegant extrusions of the body (if functionally a bit too small), and the seating position was appreciably ergonomic. Without the anxiety of researching my next plug-in location, I was free to soak in these details through the antifragile lens.

As we boarded the ferry, I felt satisfied with my initial assessment and so retreated to the 7th floor sun deck to soak in the sights and sounds of the ocean. My impromptu journey to Victoria was really just an excuse to be on the water again. Like Moby Dick’s protagonist Ishmael, I get to the sea as soon as I can whenever I start to feel like my hypos are getting the upper hand of me.

The crashing waves, punctuated by gong-like bongs of the ferry horn, washed away the day-to-day and reconnected me, nay, plugged me back in with the vastness of it all. My mind drifted from place to place, each representing a similar moment of water-induced calm. Maui, Israel, Spain, Lisbon, and back again.

The shore approaching, I returned to the Volt. One-by-one, the strings of cars disembarked onto Vancouver Island.

On the road towards Victoria, whistling away in EV mode, the ride dampening continued to impress. Flowing, smooth, and luxurious sensations filtered up through mon derrière without succumbing to excess body roll in the corners. My friend’s father, a spirited orthodontist and proud new 458 Italia owner, was equally impressed by the silence, comfort, and body control when I chauffeured him to the airport a few days later. He knows a thing or two about high-end cars and we both agreed that the Volt feels worthy of a C$50k price tag. No questions asked.

My friend’s father, a spirited orthodontist and proud new 458 Italia owner, was equally impressed by the silence, comfort, and body control when I chauffeured him to the airport a few days later. He knows a thing or two about high-end cars and we both agreed that the Volt feels worthy of a C$50k price tag. No questions asked.

Back on Vancouver Island, the drizzled roads felt congested and claustrophobic. Trying to minimize my time away from the open ocean, I made a B-line for my legislative destination, scarcely noticing the 1.4L engine buzzing with wakeful intent. Arriving at 3:30pm, I snapped a photo of the Volt in front of Parliament (as seen at the end of the article), and returned once more to the Swartz Bay terminal to await the 5pm ferry back to the mainland.

Darkness soon descended. With the black paint handsomely masking the black body mouldings, shrouding the Volt in a phantom’s cloak, the cutting red taillights were like lighthouses. The strings of cars boarded the 5 o’clock ferry, and for the next 90 minutes, I stood silently at the bow of the ship, alone, ocean spray spotting my glasses, as the ship’s spotlight communicated silently with the shore. The blackness was consuming. And connecting. The stars were the light.

Disembarking for the 2nd and final time, the strings of cars poured out of the Leviathan. Back on the mainland, I set course for Vancouver to celebrate my friend Megan’s birthday.

Disembarking for the 2nd and final time, the strings of cars poured out of the Leviathan. Back on the mainland, I set course for Vancouver to celebrate my friend Megan’s birthday.

After 142.5km of driving, seat heating, phone charging, idling, and music bumping, I arrived relaxed, refreshed, renewed, and with respect for GM’s accomplishment.

Although the Volt appears to be an intermediary technology between all-gas and all-electric, it’s far from a middling attempt. It’s not just an alternative propulsion vehicle, it’s a lifestyle vehicle in the vein of the Mercedes CLS, i.e. one that mixes practicality and performance in an eye-catching package. Through that lens, its low operating costs are icing on the cake, even if its well-to-wheel emissions continue to stir debate.

Pundits who aren’t in the market for a $50k new car have made a mountain out of the Volt’s C$42,000 (C$48,030 as tested) price tag, but it’s really no more than the far less amusing BMW 328i, with a few boxes ticked. It’s hard to think of a more eye-catching, attention-grabbing, conversation-starting, statement-making, luxurious-feeling, quasi-efficient lifestyle vehicle for the money.

It might not be ideal for a plug-inless urbanite in snowy Alberta, but for spontaneous West Coasters, the Chevy Volt is the cool, calm, and the most antifragile electric car in North America’s vast expanse.

Having a range-extending engine for the “once-in-a-whiles” isn’t optimally efficient, but the Volt is better for it. Even Nassim Taleb would approve.

[Photo credits: author, Map credit: Google]